Hebdomad

A World Historical Shitpost

by Jørgen Agosto Comgall

edited with an introduction by Ludovico Ambrosius

Copyright 2022

by Jørgen Agosto Comgall

and Ludovico Ambrosius

ISBN: 979-8-8366-8980-3

Introduction

I commend wholeheartedly to the reader the book he holds in his hands: Hebdomad: A World-Historical Shitpost, by my friend and esteemed colleague Profesor Jørgen Agosto Comgall. A few words of introductions are appropriate, both to Comgall and to his work, for neither have been made known to the public prior to this enigmatical volume, and yet both he and it are or should be world-historical figures in their own right.

Many evenings and late into the night I spent with Comgall discussing this book's principal subject, his theory of the seven ages of mankind. In a way it is simple enough to state: as there are seven ages in a man's life, there are seven ages of mankind, no more no less, and every aspect of every time and every place can be characterized as belonging to one or more of these ages. Simple to state, but containing immense complexities. Even today I do not profess to understand this theory's full significance. Comgall worked on the manuscript of Hebdomad for, it seems, perhaps one year, beginning in August '20 and breaking off abruptly in August '21. From our conversations over the last half-decade, however, it is clear that the idea had haunted him all the time that I have known him, and I suspect longer. He would occasionally vacillate on this or that aspect of the theory, but its basic structure—the seven ages, the analogies between them, projection into an imagined eighth—were invariant. I do not know (to invoke his favorite category of metaphor, the mathematical) what function his tweaks sought to maximize while preserving this invariance, and neither do I know if he deemed himself to have succeeded.

This uncertainty is not solely the result of Comgall being unavailable for questioning. Comgall's train of thought had always been momentous, singularly difficult to assess or alter, for others and perhaps also for himself. On a Friday in May '21, some months before his disappearance, he presented me with a fair copy of Part III and a request for comment. I read the draft over a weekend and that Monday returned detailed notes, but on reading the final draft I found that none of my suggestions had been incorporated, and what changes had been made were entirely orthogonal to the thrust of my objections. Yet he also sent me an elaborate letter of thanks, in which he swore that my comments had proven indispensable to the development of the hebdomadal idea. Since he may at that time have already abandoned any intention to see Hebdomad through to publication, we will never know whether he said this in earnest or only as a kind of polite fiction. From my knowledge of Hebdomad's composition the former possibility is difficult to imagine, but from my knowledge of Comgall's character the latter seems equally implausible.

I first met Comgall when I was recruited to teach at the University, at which time he was just finishing up his doctorate. Upon submission of his dissertation he was immediately offered a professorship in the philosophy of the history of philosophy of history by an all but unanimous vote, the one dissenting ballot being that of his faculty supervisor, whose complaints of perfectionism and resistance to revision were dismissed at the time as self-contradictory grumbling, but today, I must admit, seem all too plausible. At no time, nevertheless, did the St. Isidore faculty ever regret its decision. Comgall's dissertation project, a masterful interpretation of the role of the ocean in the new science of Giambattista Vico, he refused to submit to publication, declaring it irredeemably flawed. Instead, he immediately commenced work on a comparative study of St. Augustine, Vico, and René Girard, and began teaching a class focused on these three figures. It proved extraordinarily popular, among faculty as well as students, although I myself never participated.

(It is likely, I realize, that the reader is not familiar with the University of St. Isidore. Set this ignorance aside. Know simply that the University can be found in far northern California; that it has few professors, and admits fewer students; and that its eponymous saint, Isidore of Seville, was the last scholar of the ancient world, one of the first encyclopedists, and the inventor of several punctuation marks, and in an unofficial capacity has become the patron saint of the internet. As an infant, the legend goes, Isidore was lost in the vegetable garden and discovered only days later, after a swarm of bees had begun to build honeycomb inside his mouth.)

My friendship with Comgall began when he identified me as a scholar of board game design, and approached with a proposal to develop a game based on Vico's theory of the transition from the Age of Gods to the Age of Heroes. The game's rules, he insisted, must embody the severe poetry of the Twelve Tables, such that the playing of it would do more to clarify Vico's thought than a score of linear close readings. This project initiated our collaboration, but proved to contain certain insuperable difficulties (the details are unimportant) and soon fell out of view. Our talk rambled from the Dark Ages to the whaling industry to so-called "Deep Learning" artificial intelligence, about which he was in a way more optimistic than myself. From AI pedagogy we turned to Shakespeare's King Lear, and on the night of that conversation, so far as I was concerned, the Seven Ages idea was born. When we spoke it did not seem to me something he was inventing on the fly, but rather as if he had read it somewhere and sought to recall it to mind page by page, analogy by analogy, distinction by distinction; but when I asked what I should read to better understand the seven ages, he muttered, as if ashamed, that he had not yet begun to write. Some years later he made vague allusions to the effect that work had begun, while swearing me to deepest secrecy and denying vigorously that it was ready for the public eye. It is my belief that at no time before his disappearance did he share the manuscript of Hebdomad with another living soul.

I cannot reveal to the reader this book's true significance, for that significance will become entirely apparent only when the world changes utterly and the works of this age no longer live. But I can offer my own impressions.

My principal objection to the draft was its elliptical prose. To do justice to the chosen topic, I told him, would require seven hundred pages, not a bare seventy. On reflection, even that would be insufficient: each sentence of what would become Part III itself deserves a monograph. Comgall refused, however, to show his work. What he has written is not an argument based on evidence, but a set of conclusory assertions interlocking so tightly that it is sometimes difficult to imagine a single claim being altered. Yet at other times, the words seem to float so far away from their referents that they could mean almost anything at all. Based on my conversations with Comgall, I believe that he had a very clear meaning in mind for each, and indeed could have written every one of those monographs (though I cannot vouch for the scholastic integrity of the footnotes). From a close comparison of the final (I do not say finished) manuscript with the notes I took on the draft (I was not allowed to retain a copy of the draft itself), I know also that he did adjust his claims at innumerable points, often in infinitely subtle ways. I do not believe he would have wanted me to provide examples.

I must, I suppose, say a word about the title, to which I strenuously objected but on which, as on so much else, Comgall was intransigent. "Hebdomad" is clear enough, and indeed too clear, in my judgment a weak name for such a strong book. "World-Historical" names the book's topos, and insofar as it quibbles on that topos to make also a concealed boast, I for one believe the boast warranted. But "Shitpost" (alternative spelling: "Shitpoast") is unforgivable. Vulgarity aside, it seems descriptively inaccurate. In one widely available definition, a shitpost is "a post of little to no sincere insightful substance," "low effort/quality," "with the sole purpose to confuse, provoke, entertain," often "surreal [and] out-of-context," differing from "memes" in having "no template," from "spam" in not needing "repetition," from "bait" in not being "designed for response." Perhaps Comgall in his darker moments imagined all of these descriptors to apply, and certainly Hebdomad is confusing provoking entertaining surreal original inimitable. But as for low quality, subtitles are no place for self-pity or self-exculpation. And insofar as this half of the subtitle was meant not as flagellation but as boast, it does not convince: Hebdomad is surely if anything an effortpost.

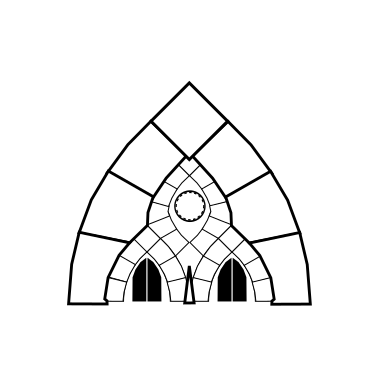

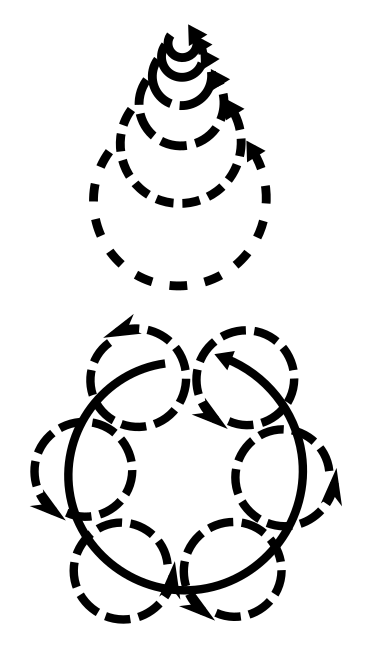

Despite my misgivings I have left Comgall's title intact, as I have every word of his manuscript, typos excepted—I have corrected several of Comgall's, and have not, I hope, introduced too many of my own (remember that the manuscript required manual transcription). I should note that the manuscript includes four poems, of which Comgall is not the writer: I am. One was written by me and previously published; Comgall read it in manuscript and, though he never asked my permission to include it, I hereby grant it freely, if such permission is required given my status as editor of this volume. The other three were written by me upon Comgall's request and at his direction, and on these he can be considered in a sense the true author. I do not know the provenance of the Frontispiece. I had not imagined Comgall to be a draftsman, but neither have I identified any business correspondence or other evidence that the piece was commissioned. The true draftsman, if it is not Comgall himself, is invited to come forward with evidence to that effect. I am uneasy critiquing a stylist who is perhaps unaware of his exposure, but I do not much care for the internet cartoon stick figure style.

After opening epigraph and picture and poem and poem, the reader of Hebdomad finally encounters a few pages of expository prose—seven paragraphs, to be precise, under the heading "What's All This Then?" Each must judge for himself the validity of Comgall's explicit philosophico-historical project, Augustine and Vico and Catholic historicism and all that. I, for one, would place less emphasis on the self-accounting of a man who seems to have been very much an enigma to himself as well as others, and more on the section immediately following, what the headers for Part I refer to as a "partial bibliography." Partial in what sense, the reader may ask? That it fails to contain every book Comgall ever read on any topic relevant to the book's argument (which is almost any topic imaginable), is obvious. That it is only the books to which Comgall was partial, is a tempting but ultimately untenable interpretation. Several of the books on the list I know, or thought I knew, Comgall to hold in quite low esteem. Perhaps some books warrant inclusion in a kind of anti-canon of philosophical history? But then one notices the absence of Marx and Spengler, despite the explicit reference to them in the previous section. I find myself entirely unable to account for their absence, except by hypothesizing that Comgall in fact had never read either of them, and scrupled to include them in a list of works referenced, despite being entirely willing to pass judgment on their work in the heat of argument.

So prose, list, and another poem; and then into Part II, almost none of whose words are Comgall's own; and then Part III, the heart of the Hebdomad project, seven surveys of the seven ages from seven different angles, all written in a kind of unrelenting allusive imagistic prose that raises more questions than it answers. Then a truncated Part IV, in which for the first time since Part I's "statement" Comgall allows us to breathe, and speaks in plain English, theoretically and practically, of how the arc of history bends into the future. Then, to close, one last poem, "The Eighth Day," not written for Hebdomad but, I agree with Comgall, oddly appropriate. I suspect, though it is the shortest, that this Part gave Comgall the most trouble of all four, for he was always happier thinking of the past than of the future. I will even admit that I would not be surprised if it was what I imagine to have been his struggles with these closing pages that led Comgall so recklessly to abandon the Hebdomad manuscript one year ago.

Comgall spent thirteen years at the University: from '08-'15 as a doctoral candidate, from '15-'21 as a professor. He disappeared in August '21, just before the beginning of the autumn term, which caused some consternation among the faculty, for the course he was scheduled to teach, on the subject of which he alone was qualified to lecture, was full and indeed oversubscribed. I believe myself to have been the last mortal soul to see Comgall alive, for on a windy day in late August I visited his house and walked with him out to the pier where he kept his boat. I am no sailor, but remember that the vessel was of fiberglass and had two parallel hulls, something like a catamaran or an outrigger canoe. The sail was furled and so I do not know its shape, but somehow I imagine it to have been triangular. The term started in ten days, and he was stocking up for an ocean voyage of at least a week, but when I inquired he insisted that he would be back in time for convocation. We walked back to his house, I put into his hands a copy of my just-published book (Roll, Strike, Die, and Other Poems, in which he could have found a version of the poem which he sought to include in Hebdomad) and we said farewell. No one has seen him since.

When Comgall did not show up to teach his class in early September the speculation began, and my last-in-time claim was quickly established. A report was filed, but after a quick search of his house and the surrounding coastline the investigation stalled. We all are convinced that he must have capsized and drowned somewhere in the vast expanse of the Pacific. Many suspect that the likelihood of such a disaster was within his knowledge, and perhaps even within his intent. For the last year his house, owned by the university and tied to his endowed chair, has been unoccupied, apart from a caretaker who cleans and dusts and the like. Perhaps fittingly, the endowment instrument indicates that it is to be filled again only after it has sat vacant for seven years.

For the next six months I tutored students in the ludic arts, prepared my hives for winter, and wrote what may be too many lines of poetry, or may be too few. At all times I tried not to think about my colleague Jørgen Agosto Comgall, who found himself lost at sea, or about the house of the Professor of the Philosophy of the History of the Philosophy of History, sitting empty only a few blocks from my own, or about the Hebdomad manuscript which I knew lay unread within it, accumulating dust which every few weeks would be brushed away by one entirely ignorant of its importance. Eventually curiosity outweighed reluctance, and a few months ago I used the key Comgall had lent me to enter his house and remove the manuscript from his desk. I found there also the frontispiece wrapped in tissue paper, and instructions regarding the volume's intended layout. Given the understanding that existed between us concerning his work, I did not and do not consider this any form of larceny. On reading it I reached the conclusions mentioned above concerning Comgall's habits of revision; I also realized that the true crime would be failing to publish Hebdomad simply because we do not know Comgall's intentions regarding the manuscript.

The genius of Hebdomad, as you are about to see, does not lie in the bare schema of seven ages, summarized in an instant, but in the virtuoso pattern Comgall weaves upon that septuple framework, in a feat which proves the framework competent to bear the strain of history. To follow that pattern some knowledge of every historical age will be helpful (and the more history one knows the more intricate the pattern will appear), but such knowledge is hardly a precondition, any more than it is a precondition to absorbing a false historical outlook, whether through belief in a "Dark Ages," a "State of Nature," or a moment when "we became modern." Comgall struggles somewhat in Part I to describe the purpose of his project. I would put it like this: knowing well that history follows myth, Comgall offers us a historical mythology worthy of our historical moment. So long as this moment is remembered, I trust that Hebdomad will not lack for readers.

Ludovico Ambrosius

University of St. Isidore

August 2022

I

*

All the world's a stage,

And all the men and women merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances,

And one man in his time plays many parts,

His acts being seven ages. At first, the infant,

Mewling and puking in the nurse's arms.

Then the whining schoolboy, with his satchel

And shining morning face, creeping like snail

Unwillingly to school. And then the lover,

Sighing like furnace, with a woeful ballad

Made to his mistress' eyebrow. Then a soldier,

Full of strange oaths and bearded like the pard,

Jealous in honour, sudden and quick in quarrel,

Seeking the bubble reputation

Even in the cannon's mouth. And then the justice,

In fair round belly with good capon lined,

With eyes severe and beard of formal cut,

Full of wise saws and modern instances;

And so he plays his part. The sixth age shifts

Into the lean and slippered pantaloon,

With spectacles on nose and pouch on side;

His youthful hose, well saved, a world too wide

For his shrunk shank, and his big manly voice,

Turning again toward childish treble, pipes

And whistles in his sound. Last scene of all,

That ends this strange eventful history,

Is second childishness and mere oblivion,

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.

– William Shakespeare, As You Like It

*

Table of Contents

Hebdomad, the book you hold, holds wisdom of a lifetime.

For as the lifetime of a man proceeds through seven stages,

So the Life of Man through seven ages does extend.

This Hebdomad reveals for the first time these subdivisions,

And how they resonate and ring and rhyme with one another.

The book reveals sequentially these seven's many aspects,

Some sevens I'll lay out for you as this book does proceed.

Imagine each age in its own exemplary place and time;

With its own architecture, mathematics, music, art,

Its language and the flourishes that flourish there within;

Each has its map of true and false, of mind and beast and man,

And various masks to represent the persons on the board;

Imagine, you, that is to say, the seven sevens here.

Afric – Egypt – Roman – Europe – 'Tlantic – 'Merica – Space

Fire – Altar – Temple – Cathedral – Meeting-house – City – Diode

Speech – Picture – Writing – Codex – Type – Telegraph – Signal

Animal – Dual – Causal – Triune – Ration – History – Ego

Mask – Seal – Coinage – Arms – Flag – Logo – Avatar

Communal – Hierarch – Civic – 'Clesial – Private – Abstract – Sole

Prime – Archaic – Classic – Midst – Modern – Mod'ist – Contempo

His Acts Being Seven Ages

I

A flood, they sing, then a prismatic bow.

The waters ebb away. Round flickering fires

The people huddle closely with their kin,

Whisper of other blood beyond the trees.

They couple without law, not without sin,

Feel skin pierced through by forest's thorns and briars,

Know not of times to reap or times to sow.

II

Then: cryptic hieroglyphics paint a scene

Of megaliths built up to greet the stars,

The peace of god-kings levying their corn

And their daughters to feed and bed his guards.

Gold rings and golden carcanets adorn

Unseen immortals. In their brazen cars

The shepherds leave a waste to cross the sea.

III

Accounting births chirography, divorces

Empire from wisdom's higher institute.

Each sovereign pays a soldier to secure

Slaves to mine silver for the mint; meanwhile

Across the square monologist seeks cure

For double death, blinking its absurd root—

But one man yokes the base and noble horses.

IV

So: bind his words in codices, and raise

Them high before the sacramental rose!

Beneath petrific forest canopy

Endlessly ring them round the amorous fires.

Love's debt forborn, and in full panoply,

Depart the manors, face the paynim foes:

These double swords the chessboard cannot faze.

V

Till Presses start—a Fraktured Revolution

Encompasses the World in Caravels—

Encounters peoples Queer and Cannibal—

In austere clapboard Houses mercantile

Frames between Characters compatible

Sweet Dialogue—and when the Heart Rebels,

Defaults back to a dubious Constitution.

VI

BLOODY BATTLE ABROAD / the wires scream

Across the sky / as towers / rise to scrape

Maximal value from the / abstracted corpse

Of billennia-old land / / urban vanguards

Imbibe ideas / from the ironworks

Poised / exquisitely / twixt raze and rape

Analyzing within / a shifting scheme

VII

Now time closes itself. Numbed fingers glide

By hidden laws across a flickering screen

To choose a solitude from perverse lack

And lawlessness. Now each does as they please.

But soon… forgetting shatters in a crack…

A slice… a pain… from forests of protein

Gene-skeins of death loose in the hematic tide…

What's All This Then?

To subitize—some experimental psychologists decided in 1949—means to look at an array of objects and simply know, without counting, how many there are. Scatter one, two, three, perhaps four items on a table, and take a glance at them, subito. In the blink of an eye you'll know how many items are there—one, or two, or three, or four. But any more, and it gets tricky, and eventually impossible. Imagine a four by four array of items. On seeing it you'll immediately know that it's four by four, but it'll take another half-beat of the pulse before you hear yourself think "sixteen." In between, in depends. Five items in a pentangle; six in a two by three array; seven in a hexagon with center point—for these subitizing may be possible. But they have to be arranged just right, or you'll have to stop and count.

This book arranges historical heptads so that they can be seen without stopping to count. This does not make its argument a historical one. Part II has a historical character but is less argument than anthology, consisting of seven extracts from seven distinct texts. Part III makes an argument, or at least tells a story, but is not history because apart from the stage-setting first section, "Time—Place—Manner," it contains almost no particulars. Whenever a proper name is mentioned, the intent is not to inform the reader, but to recall to mind some well-known complex of events, images, impulses, ideas—in short, to serve as a kind of shorthand. Apart from these allusions, the book speaks entirely in generalities. Shakespeare, drawing on a long tradition of archetypal partitions of the human lifespan, gives us the Infant, the Schoolboy, the Lover, the Soldier, the Justice, the Pantaloon, the Second Child. This book offers a parallel seven, referred to, for reasons described in Part III's final section, "Terms—Histories—Eternities," as the Primitive, the Archaic, the Classical, the Medieval, the Modern, the Modernist, the Contemporary. Upon completing this book the reader should begin to recognize these seven at play wherever he looks.

The idea of dividing history into various ages, each following inexorably from the one proceeding, is of course an old one. The Greeks spoke of ages of gold, silver, bronze, iron, declining gradually from greatness, peace, and contentment to weakness, violence, and suffering, the latter being the lot of the present day. The metallic metaphor hinted at the possibility of a natural cycle, a renewed golden age to rise from the decadent mud, as it had uncountably many times before. This book takes for granted that any effort to revive the Golden Age mythology, to dwell in dreams of Atlantis or Hyperborea, will be no more successful among the very online of today than among the decadent theosophists of a hundred years ago. The early Christians spoke of six ages, accounting them in terms of salvation history: Adam to Noah, Noah to Abraham, Abraham to David, David to the Babylonian Captivity, the Captivity to Christ, Christ to the present; as the Christian era wore on a tripartite division became more common: Adam to Moses, Moses to Christ, Christ to the present; that is, natural law, Mosaic law, the law of love. The Christian approach could admit no cycles, but it too thought the present day at the end of the sequence. This Salvation History mythology has more to recommend it, but given the dramatic developments of the last seven hundred years, its insistence that history ended in 33 AD cannot fully satisfy.

This book's seven-part sequence differs from the Classical Greek and Christian schemata in many ways. Most important, perhaps, is that it does not distinguish its members from one another primarily with reference to some scalar quantity "greatness remaining" or "revelation completed," with the present necessarily possessing the maximum or minimum amount. Rather, it shows how the ages differ from one another in every aspect. Which is not to say that there are no larger patterns. Two such patterns are particularly worth mentioning. First, the sequence is chiasmic. The Contemporary in many ways parallels the Primitive; the Modernist, the Archaic; the Modern, the Classical; while the central Medieval era has something in common with all three pairs. Second, the movement of history does turn out to have something like a direction, an increase in one quality and corresponding decrease in its opposite. But this quality is not grasped from our experience of the world and projected back into our fantasies about some earlier time. Rather, it emerges from contemplation of the schema itself. Different heptads sketched in Part III will suggest different aspects of this overarching trajectory: in "Architecture, Mathesis, Music, Mimesis," a shift from openness to closure; in "Interpretations," a shift from spirit to matter; in "Energy, Family, Finance, Violence," a shift from male to female.

These features align this book's seven-part schema less with Classical accounts of the ages of the world, and more with Modernist accounts of the ages of human civilization. The latter differ from the former in that they do not treat historical change as having an external cause, natural or divine, unchanging in its operation and so having as its direct effect the filling up or draining of some reservoir. Rather, historical change results from the unfurling of the logic of human consciousness through human action within an inhuman world; the only constant is that it is always humanity at work. By far this book's greatest influence has been Giambattista Vico, author of The New Science. Its first three ages, Primitive, Archaic, and Classical, are borrowed wholesale from Vico with only minor modification, while its fourth and fifth, Medieval and Modern, in large part respond to Vico's perhaps overly simplistic theory of the ricorso, of decadence leading to civilizational collapse and so a return to the beginning of the three-age cycle. This book departs from Vico, that strange lonely figure of the Neapolitan Enlightenment, born both too early and too late, in that it does not understand history ever to repeat itself, although it does rhyme. This book aims to suggest that the fourth age rhymes most of all.

This book is not an endeavor in philosophy of history. But some explanation should be offered for the exaltation of Vico over his better-known successors in historicism. Hegel's triad of thesis, antithesis, synthesis, is entirely too optimistic about the potentialities of Reason alone, as one would expect from an author writing early in the Modernist phase. Spengler's late Modernist tetrad of spring, summer, autumn, winter, in contrast, is entirely too pessimistic, a kind of naive empiricism bewitched by natural science. That central Modernist Marx has a somewhat plausible five-stage economic history—tribalism, slavery, feudalism, mercantilism, capitalism—which this book borrows with modification, tacking on a first and last, but his prognostications are dubious, and this because he overestimates his ability to reduce the movement between these stages to a purely material cause, and, further, oversimplifies the nature of that material. This book does take the means of production seriously, while emphasizing as well, following McLuhan, the means of communication—see Part III's "Language & Literature"; and, following Girard, the means of sacralization—see Part III's "Persons & Performances." But whether economic, informational, or libidinal, determinism is an error, for it requires stipulating some objectively unchanging feature of the human mind, and so is necessarily dehumanizing. The book solely attends to what Vico calls "the modifications of the mind of him who meditates."

Vico, McLuhan, and Girard together constitute a tradition of Catholic historicism, to which this book is indisputably an heir. A fourth member of the tradition, and another substantial influence though his work bears less directly on the question at hand, is John Henry Newman, who theorized the development, as opposed to the evolution, of theological ideas. Such historicism accepts the monotonicity of Salvation History, but sees the Resurrection not to end history so much as to inaugurate a new phase, one whose complexity is still unfolding. To reduce from seven ages to three the Catholic historicist would put the boundaries at the Crucifixion and the discovery of the Americas. But such a triad would be far less enlightening. The purpose of this book is not to be true—an interpretation can never be true or false—but rather to shed light, to make the heptads visible. Once you can see them, you can decide for yourself what they tell us about what we have done, and what we are doing, and what we will do. Part IV offers further reflections on the subject of what, if anything, we can hope will succeed the seventh age.

A Selection of Works Referenced

Moses, Pentateuch (c. 1310 BC)

Plato, Timaeus (c. 380 BC)

Augustine of Hippo, The City of God (c. 420 AD)

Isidore of Seville, Etymologies (c. 620 AD)

Dante Alighieri, Divine Comedy (1308-20)

William Shakespeare, Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies (1621)

Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan (1651)

Giambattista Vico, The New Science (3rd ed. 1744)

William Blake, Jerusalem (1820)

Thomas Carlyle, Sartor Resartus (1834)

Wilhelm Gottfried Hegel, Introduction to the Philosophy of History (1837)

John Henry Newman, Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine (1845)

Herman Melville, Moby-Dick; or, the Whale (1851)

Orestes Brownson, The American Republic (1866)

Lev Tolstoy, War and Peace (1869)

Friedrich Nietzsche, The Genealogy of Morals (1888)

Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1905)

Henry Adams, The Education of Henry Adams (1907)

Walter Lippmann, Drift and Mastery (1914)

Johann Huizinga, The Autumn of the Middle Ages (1919)

Georg Lukacs, The Theory of the Novel (1916)

Sigmund Freud, Civilization and its Discontents (1930)

Erik Peterson, Monotheism as a Political Problem (1935)

Erich Auerbach, Mimesis (1946)

Mircea Eliade, The Myth of the Eternal Return (1949)

Carl Jung, Foreword to the I Ching (1949)

E.K. Kaufman &c, The Visual Discrimination of Number (1949)

Erwin Panofsky, Gothic Architecture and Scholasticism (1951)

Eric Voegelin, The New Science of Politics (1952)

David Jones, The Anathémata (1952)

Northrop Frye, Anatomy of Criticism (1957)

Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition (1958)

William F. Lynch, S.J., Christ and Apollo (1960)

Marshall McLuhan, The Gutenberg Galaxy (1962)

Frank Kermode, The Sense of an Ending (1967)

Kenneth Clark, Civilisation (1969)

Alan John Villiers, Men, Ships, and the Sea (1973)

René Girard &c, Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World (1978)

Stanley Cavell, Pursuits of Happiness (1981)

Walter J. Ong, S.J., Orality and Literacy (1982)

Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities (1983)

Walker Percy, Lost in the Cosmos (1983)

Alisdair MacIntyre, Whose Justice? Which Rationality? (1988)

Charles Sellers, The Market Revolution (1991)

James Conant, The Search for Logically Alien Thought (1991)

Gene Wolfe, The Solar Cycle (1980-2001)

Miguel Tamen, Friends of Interpretable Objects (2001)

Sarah Beckwith, Signifying God (2001)

Remi Brague, Eccentric Culture (2002)

Brett Bourbon, Finding a Replacement for the Soul (2004)

Stephanie Coontz, Marriage, a History (2005)

Robin Hanson & Eliezer Yudkowsky, The AI Foom Debate (2009)

David Graeber, Debt (2011)

Thomas Pfau, Minding the Modern (2013)

Matthew Weiner, The Romanoffs (2018)

Ross Douthat, The Decadent Society (2020)

Scott Alexander, Slate Star Codex (2013-20)

Jan Lucassen, The Story of Work (2021)

Zero HP Lovecraft, They Had No Deepness of Earth (2018-21)

The Author Apologizes for His Ambition

Cataloguing caveats

Drowns the thinks in the think nots.

"Hundred thousand years ago

Man wandered the Siberian snow";

"Myriad years he sowed his seed

By Tigris, Ganges, and Yangtze";

"Roma conquered the known world,

But the map hadn't yet unfurled."

And "Europe's mere peninsula,

Minor, off great Eurasia";

And "Red Injuns were there before

Invaders showed up at their door";

And "All America's hijinks

Aside, the world's full of Chinks."

"Only the far too online NEETs

Think twitter's realer than the streets."

What of it? If I simplify

The multitudes, I simplify

To concentrate the weary mind

On the grand tale of humankind.

One thing, though, Shakespeare got wrong

In Jacques's captivating song:

The seven parts each man must play

He plays together. When we lay

And mewl and puke in nurse's arms,

Already looms there the alarms

We'll set off when the darkling plain

We sweep across; and yet again

Just look to see the oblivion

We'll feel while teeth, eyes, taste, are gone;

Schoolboy, lover, justice, scholar,

There, but in a frame made smaller

From being lately in the womb.

'Stead of a tour room to room,

Think how, within a single face,

Considering one side you trace

'Cross the brow and lower jaw

Devise of the father's pa;

Then from the other, in the nose,

The clear aspect of one who knows;

From the front the lips shout out

Mother's sister's famous pout.

My project's not taxonomy,

But human physiognomy—

Not a death-mask lifted from

The last man's face gone cold and numb

But breathing, living portraiture

Of Man and his ten-and-three-score.

Only this? And Nothing. More.

II

*

*

And the Lord spake unto Moses, saying, Speak unto the children of Israel, that they bring me an offering: of every man that giveth it willingly with his heart ye shall take my offering.

And this is the offering which ye shall take of them; gold, and silver, and brass, And blue, and purple, and scarlet, and fine linen, and goats’ hair, And rams’ skins dyed red, and badgers’ skins, and shittim wood, oil for the light, spices for anointing oil, and for sweet incense, onyx stones, and stones to be set in the ephod, and in the breastplate.

And let them make me a sanctuary; that I may dwell among them. According to all that I shew thee, after the pattern of the tabernacle, and the pattern of all the instruments thereof, even so shall ye make it.

And they shall make an ark of shittim wood: two cubits and a half shall be the length thereof, and a cubit and a half the breadth thereof, and a cubit and a half the height thereof. And thou shalt overlay it with pure gold, within and without shalt thou overlay it, and shalt make upon it a crown of gold round about. And thou shalt cast four rings of gold for it, and put them in the four corners thereof; and two rings shall be in the one side of it, and two rings in the other side of it. And thou shalt make staves of shittim wood, and overlay them with gold. And thou shalt put the staves into the rings by the sides of the ark, that the ark may be borne with them. The staves shall be in the rings of the ark: they shall not be taken from it. And thou shalt put into the ark the testimony which I shall give thee.

And thou shalt make a mercy seat of pure gold: two cubits and a half shall be the length thereof, and a cubit and a half the breadth thereof. And thou shalt make two cherubims of gold, of beaten work shalt thou make them, in the two ends of the mercy seat. And make one cherub on the one end, and the other cherub on the other end: even of the mercy seat shall ye make the cherubims on the two ends thereof. And the cherubims shall stretch forth their wings on high, covering the mercy seat with their wings, and their faces shall look one to another; toward the mercy seat shall the faces of the cherubims be. And thou shalt put the mercy seat above upon the ark; and in the ark thou shalt put the testimony that I shall give thee.

And there I will meet with thee, and I will commune with thee from above the mercy seat, from between the two cherubims which are upon the ark of the testimony, of all things which I will give thee in commandment unto the children of Israel.

*

SOCRATES: Then have I now given you all the heads of our yesterday's discussion? Or is there anything more, my dear Timaeus, which has been omitted?

TIMAEUS: Nothing, Socrates; it was just as you have said.

SOCRATES: I should like, before proceeding further, to tell you how I feel about the State which we have described. I might compare myself to a person who, on beholding beautiful animals either created by the painter's art, or, better still, alive but at rest, is seized with a desire of seeing them in motion or engaged in some struggle or conflict to which their forms appear suited; this is my feeling about the State which we have been describing. There are conflicts which all cities undergo, and I should like to hear some one tell of our own city carrying on a struggle against her neighbours, and how she went out to war in a becoming manner, and when at war showed by the greatness of her actions and the magnanimity of her words in dealing with other cities a result worthy of her training and education. Now I, Critias and Hermocrates, am conscious that I myself should never be able to celebrate the city and her citizens in a befitting manner, and I am not surprised at my own incapacity; to me the wonder is rather that the poets present as well as past are no better—not that I mean to depreciate them; but every one can see that they are a tribe of imitators, and will imitate best and most easily the life in which they have been brought up; while that which is beyond the range of a man's education he finds hard to carry out in action, and still harder adequately to represent in language. I am aware that the Sophists have plenty of brave words and fair conceits, but I am afraid that being only wanderers from one city to another, and having never had habitations of their own, they may fail in their conception of philosophers and statesmen, and may not know what they do and say in time of war, when they are fighting or holding parley with their enemies. And thus people of your class are the only ones remaining who are fitted by nature and education to take part at once both in politics and philosophy. Here is Timaeus, of Locris in Italy, a city which has admirable laws, and who is himself in wealth and rank the equal of any of his fellow-citizens; he has held the most important and honourable offices in his own state, and, as I believe, has scaled the heights of all philosophy; and here is Critias, whom every Athenian knows to be no novice in the matters of which we are speaking; and as to Hermocrates, I am assured by many witnesses that his genius and education qualify him to take part in any speculation of the kind. And therefore yesterday when I saw that you wanted me to describe the formation of the State, I readily assented, being very well aware, that, if you only would, none were better qualified to carry the discussion further, and that when you had engaged our city in a suitable war, you of all men living could best exhibit her playing a fitting part. When I had completed my task, I in return imposed this other task upon you. You conferred together and agreed to entertain me to-day, as I had entertained you, with a feast of discourse. Here am I in festive array, and no man can be more ready for the promised banquet.

*

*

SCENE VI. Another room in the Castle.

Enter Horatio and a Servant.

horatio:

What are they that would speak with me?

servant:

Sailors, sir. They say they have letters for you.

horatio:

Let them come in.

[Exit servant.]

horatio:

I do not know from what part of the world

I should be greeted, if not from Lord Hamlet.

Enter Sailors.

first sailor:

God bless you, sir.

horatio:

Let him bless thee too.

first sailor:

He shall, sir, and't please him. There's a letter for you, sir. It comes from th'ambassador that was bound for England; if your name be Horatio, as I am let to know it is.

horatio:

[Reads.]

'Horatio, when thou shalt have overlooked this, give these fellows some means to the King. They have letters for him. Ere we were two days old at sea, a pirate of very warlike appointment gave us chase. Finding ourselves too slow of sail, we put on a compelled valour, and in the grapple I boarded them. On the instant they got clear of our ship, so I alone became their prisoner. They have dealt with me like thieves of mercy. But they knew what they did; I am to do a good turn for them. Let the King have the letters I have sent, and repair thou to me with as much haste as thou wouldst fly death. I have words to speak in thine ear will make thee dumb; yet are they much too light for the bore of the matter. These good fellows will bring thee where I am. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern hold their course for England: of them I have much to tell thee. Farewell.

He that thou knowest thine, HAMLET.'

Come, I will give you way for these your letters,

And do't the speedier, that you may direct me

To him from whom you brought them.

*

It was a Saturday night, and such a Sabbath as followed! Ex officio professors of Sabbath breaking are all whalemen. The ivory Pequod was turned into what seemed a shamble; every sailor a butcher. You would have thought we were offering up ten thousand red oxen to the sea gods.

In the first place, the enormous cutting tackles, among other ponderous things comprising a cluster of blocks generally painted green, and which no single man can possibly lift—this vast bunch of grapes was swayed up to the main-top and firmly lashed to the lower mast-head, the strongest point anywhere above a ship's deck. The end of the hawser-like rope winding through these intricacies, was then conducted to the windlass, and the huge lower block of the tackles was swung over the whale; to this block the great blubber hook, weighing some one hundred pounds, was attached. And now suspended in stages over the side, Starbuck and Stubb, the mates, armed with their long spades, began cutting a hole in the body for the insertion of the hook just above the nearest of the two side-fins. This done, a broad, semicircular line is cut round the hole, the hook is inserted, and the main body of the crew striking up a wild chorus, now commence heaving in one dense crowd at the windlass. When instantly, the entire ship careens over on her side; every bolt in her starts like the nail-heads of an old house in frosty weather; she trembles, quivers, and nods her frighted mast-heads to the sky. More and more she leans over to the whale, while every gasping heave of the windlass is answered by a helping heave from the billows; till at last, a swift, startling snap is heard; with a great swash the ship rolls upwards and backwards from the whale, and the triumphant tackle rises into sight dragging after it the disengaged semicircular end of the first strip of blubber. Now as the blubber envelopes the whale precisely as the rind does an orange, so is it stripped off from the body precisely as an orange is sometimes stripped by spiralizing it. For the strain constantly kept up by the windlass continually keeps the whale rolling over and over in the water, and as the blubber in one strip uniformly peels off along the line called the "scarf," simultaneously cut by the spades of Starbuck and Stubb, the mates; and just as fast as it is thus peeled off, and indeed by that very act itself, it is all the time being hoisted higher and higher aloft till its upper end grazes the main-top; the men at the windlass then cease heaving, and for a moment or two the prodigious blood-dripping mass sways to and fro as if let down from the sky, and every one present must take good heed to dodge it when it swings, else it may box his ears and pitch him headlong overboard.

One of the attending harpooneers now advances with a long, keen weapon called a boarding-sword, and watching his chance he dexterously slices out a considerable hole in the lower part of the swaying mass. Into this hole, the end of the second alternating great tackle is then hooked so as to retain a hold upon the blubber, in order to prepare for what follows. Whereupon, this accomplished swordsman, warning all hands to stand off, once more makes a scientific dash at the mass, and with a few sidelong, desperate, lunging slicings, severs it completely in twain; so that while the short lower part is still fast, the long upper strip, called a blanket-piece, swings clear, and is all ready for lowering. The heavers forward now resume their song, and while the one tackle is peeling and hoisting a second strip from the whale, the other is slowly slackened away, and down goes the first strip through the main hatchway right beneath, into an unfurnished parlor called the blubber-room. Into this twilight apartment sundry nimble hands keep coiling away the long blanket-piece as if it were a great live mass of plaited serpents. And thus the work proceeds; the two tackles hoisting and lowering simultaneously; both whale and windlass heaving, the heavers singing, the blubber-room gentlemen coiling, the mates scarfing, the ship straining, and all hands swearing occasionally, by way of assuaging the general friction.

*

III

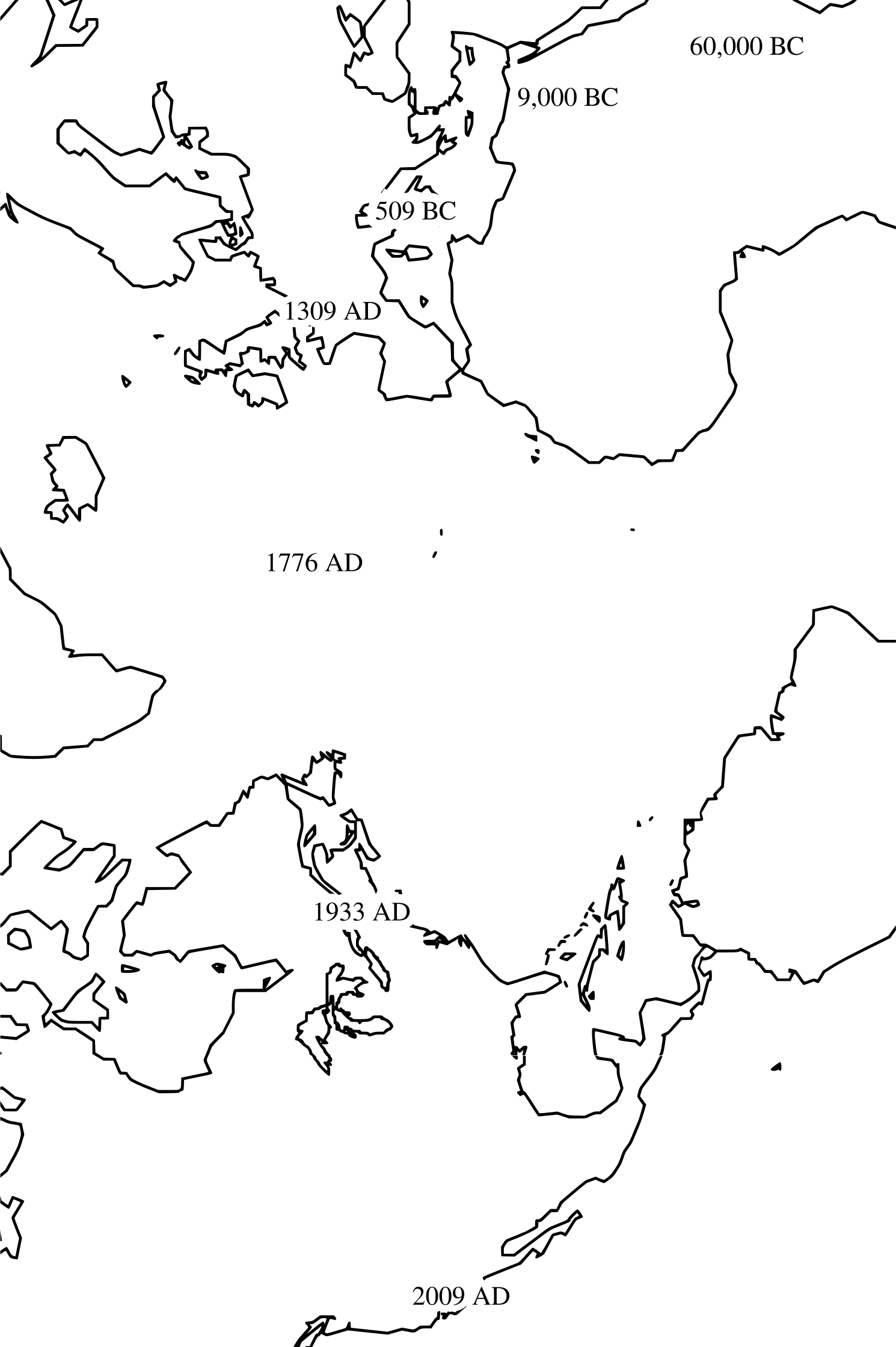

Time—Place—Manner

When does man find himself, and where, and how will he leave it behind?

Sixty millennia ante Christe natum. Rains fall in the highlands. The infant man: by the shore of a great lake, naming the animals; with a stone axe, hollowing out a floating log; in a garment of roughly sewn hides, diving into the water. He drifts downriver, into the unknown world.

Nine thousand years ante Christe natum. Glaciers melt, the Nile rises and falls. The children of Noah: harvesting barley in sweat-soaked linen tunic; hauling copper-chiseled slab to flat-bottomed barge; numbering the stars arcing over the fertile world. Against the dawn horizon, the nomadic herds.

Five hundred nine years ante Christe natum. Palaces collapse, bright bronze drowns in clamor of iron. Across the middle sea, the romance of Rome: hugging the coast in a shallow-keeled vessel; shipping grain from city to imperial city; chained to the three banks of oars, in the shadow of the trireme's sail, finding the whole world at peace. Rats scurry in the bilges.

Thirteen hundred nine anno Domini. Empire crumbles, its spirit lives on in manor and monastery, knight errant and mendicant. The fury of the martial Frank: in a high-masted hulk passing Gibraltar; curving north along Europe's western edge; heading inland up a broad river flanked by fields of wheat. The world divided, reflected back upon itself: back to open water.

Seventeen hundred seventy-six anno Domini. A deep-keeled caravel braves the unknown Atlantic and almost by accident doubles the world, three quarters ocean. Magistracy of the common Anglo: guarding the vessel with black powder cannon; filling it with salable goods; circulating on the trade winds. The land scorches his feet.

Nineteen hundred thirty-three anno Domini. America, a great machine that moves of itself. Clown-emperor America: from under the land, burning the fossilized remnant of deep antiquity; in power-woven cotton uniform, flooding its image across the world. A global frontier obliterates all islands.

Two thousand nine anno Domini. The foggy, hardly visible western shore. Dotage of the Bugman: sitting behind a glowing screen, processing data, draping garish synthetic fabrics across feeble flesh. In a flurry of silicon and rocket fuel, he aims to leave the world behind.

Architecture, Mathesis, Music, Mimesis

What kind of world does man build? How does he measure it? With what sounds does he fill it? With what images imitate it?

Man did not at first build a world; he only cleared a space for himself in the midst of the wilderness. If he built a hut or a lean-to from woven grasses, or even a more durable structure from rocks and trees, it was only a kind of temporary shelter. His soul slept always beneath a totally open sky. Whatever roof kept the rain from his body would not outlive him.

If he had a world, it was a world of names. In being a world of names, it was a world of numbers. One, two, three, four. One and two and three and four. These named both the fingers on his hand and the things the fingers named.

He put out his fingers, clapped his hands, stamped the ground, beat time against a hollow log. The people moved in unison, dancing to the rhythm of the drum, an intimidating ecstasy to drive away the evil spirits from the bodies of the dead. One, two, three, four.

What outlived him is what had preceded him: the sheer cliff faces and bare cave walls on which, generation after countless generation, he chalked a handprint, a stick-figure hunter, the beasts of the chase. In the caves, in the flickering torchlight, they would move as if alive—and then what? Would he speak to them? Or they to him?

Then he raised stones up from the ground to point to the sky—to measure it, to enter it, to defy it. Faceless hordes of unremembered menials dug the channels, pulled the ropes, piled the mud-ramps, however the megaliths came to where they now lie. Then, climbing to the tower's highest point, in word if not in deed, the hierophant would stand exposed to the terrible heavens, but fixed in place, centered like a cyclopean eye.

He grew adept at numbers and the movement between them. Adding, subtracting: how much more or less in the granary today than yesterday? Multiplying, dividing: what harvest to expect from the seeds planted in the ground, how to distribute it among the people? He developed the movement into an abstruse art: how to track the movements of the celestial bodies, identify the fixed paths of the wanderers?

Music, too, because an abstruse art; the ratios between the notes were calculated; instruments began to be devised in accordance with them, flutes and panpipes and zithers. They echoed on earth the music of the spheres.

On the sides of the stones, or in secret channels burrowed between them for the burial of the dead, he would chisel and paint the holy images, stylized to the point of grotesquerie, not an image so much as a picture-sign, an ear, a hand, a foot.

When he began truly to work in stone, he made it take human shape. Each column stood, proportioned as a man in height to width; the colonnade enclosed the temple's interior like a phalanx. From within he could look out to where the sky met the horizon, or look instead to the gabled roof that shaded him from the full glare of the high heavens.

The shape of numbers in the human mind became a problem to be mapped. Geometry advanced from an adjunct to architecture to the status of a science: how to move ineluctably from these definitions and postulates to these constructions; how to project number out into time and space from the human mind, and back again.

The celestial pretensions of music, meanwhile, came under a productive suspicion. The various scales and modes of music were analyzed for their effects on the spirit; ordered sound was harnessed for earthly purposes. From a concomitant of hieratic ritual it became a tool of humane entertainment and political manipulation.

Within the temples the columns took the very shape of man, of man's body as it ought to be, the ideal form of brow and breast and thighs; and he would paint or tile the same beauty into the ceiling, the walls, the floor. But on certain display pieces in the palaces and villas he would show their real shape, frown and wart and wrinkle, for their honest friends to recognize.

At last he grew into an architecture of pointed arches, columns piled atop forests of buttressed columns, reaching out to entwine across the ceiling's ribbed vault. Above all he reveled in the height of it. The windows—these, too, arched to an arbitrary point—he glazed in brilliant hues, and so the sky entered the cathedral and yet did not invade it so much as lend it a heaven of its own.

With the fractured glass of the windows, number fractalized from the visual to the purely intellectual. From geometry to algebra; from re-constructing a known shape to tracing the infinite contours of an unknown and unknowable quantity.

Forms of chant accompanied the performance of religious duties, and forms of musical notation were developed to annotate those duties' rubrics. Soon plain chant gave way to polyphonic overlaying of various voices pursuing harmonically related melodic lines.

In the windows, in the columns' stone, on gilded wood, he composed likenesses of the holy saints, without heroic musculature but serene and supple, at first glance expressionless with eyes expressing God. These were not seen through the icons' flat surface or the motley of stained glass, but seen in them.

Then he recoiled into the austerity of the straight line and the right angle. At times he would insist on a meetinghouse no more noble than a barn, so long as the walls were whitewashed and the ceiling broad enough to hold the entire congregation. When he felt more self-important he resorted to a neoclassical grammar bleached into sparkling blankness, and no longer an open colonnade so much as a closed white marble wall.

From this austerity and abstraction new modes of calculation were born. The mutable became susceptible of mathesis; not knowing quite how he did it, he found himself tracing the movement of movement, or moving to the size of a thing from the movement around it.

And from the keyboard, extended from organ to harpsichord, piano, new concepts of music were born—a music where the source of the sound was hidden from the player, who knew it only from the air it displaces; a music where the mechanical notes follow no organic harmony but have been calculated beforehand according to irrational formulae.

Beside these unrevealing music boxes, within his otherwise undecorated halls, he hung canvases of their black-suited bourgeois founders and funders, or of the dramatic histories he aspired to relive, and benches on which to sit and contemplate both.

Soon the breadth and height of the built world became for him not expressive of the world's design so much as the design itself. Iron rails pressed the city in on itself, steel girders pierced the skyline, and soon, when he entered the megalopolis at ground level, he could see nothing of the heavens but their cylopean eye staring down at him from straight above.

The city of mathematic knowledge, too, expanded upwards until its one-time celestial anchor was hardly visible. Theorems multiplied beyond what even the wisest could grasp unaided, and a question arose whether even something as seemingly fundamental as arithmetic reasoning had any real foundation, or was no more than a house of cards.

Too, as the production of sound expanded beyond what even the most sensitive ear could harmoniously intuit, a quest began among those who sold entertainment to the music halls of the bourgeoisie to give it some other atonal basis, expressive or abstract or introspected.

In the same bohemian garrets the priests of art invented, invented, reinvented arrangements of color and line to express the fate of the human corpus in this most inventive age.

And now, has man any world to speak to, to speak to him? The city hums around him but he does not hear it; the sky looms above him but he does not feel it; his gaze has been totally enclosed within the screen he holds in his pocket.

A mathematical foundation of sorts was found—not, as had been hoped, in theory, but in practice. The digital computer's prodigious ability to encrypt and decrypt numeric codes, and to predict the optimal courses of action without even the transfer of information, allowed mathematics to run of its own accord, an agent without a principal, into various inhuman esoterica.

So music became something less for men than for machines; not the voicing of a word, but the layering of sound upon synthesized sound, to be invoked ad nauseum whenever someone wishes to hear it, from earbuds pressed into the hollows of his ear.

The patterned meshes on the screen in his pocket project a false flickering that yet captures the world's motion better, he imagines, than does the world itself. From the corner of his eye he sees rain strike the window; he hears nothing to calm his agitated soul; he turns on Rain Sounds (Eight Hours), and goes to sleep.

Language & Literature

How does man communicate the contents of his mind? What imaginative form do those contents take?

Speech. Birthed in exclamation and injunction, man's tongue soon grew accustomed to nomination and description. He had a prodigious head for words, having nowhere else to put them. Though "words," plural, is not the right one, implying segmentation. No clear line demarcated one part of speech from another; no ironic tweezers plucked one out from the rest and held it up to the light. When a word shifted the entire world shifted, with no vantage point from which to tell before from after. His volubility answered only to itself.

No literature, as yet, because no letters, but wisdom sustained within the communal memory. Herb-lore, cloud-lore, ghost-lore, whatever learning a man might need that on his own he would acquire only too late. Relayed in songs, in catalogues, in tales of heroes and tricksters who may or may not once have walked the earth, but whose exploits could still be seen in every oddly shaped rock and every bend in the river. Every word a fable.

The pictograph. A mere mnemonic device, as he used it at first, but even so a mental revolution, once it turned from an image evoking the thing to a sign invoking the word. The verbal flux crystallized into dried pigment on stone. Now the word could not float vaguely between its referents, but required a paradigm case; different but related things required different but related words. Too, now man's grasp of lore could be tested, not against the grasp of his companions, but against the resistance of a stone face to the eroding sands. Soon the lore came to seem something out there, different both from its object and from the subject who recited it.

Man imagined now a new kind of learning: word-lore, which is to say, world-lore. Not preserving the hard-won wisdom of experience, but discovering the order lurking within all that wisdom. Further, he imagined a new way of speaking it: not improvised from the singer's sense of the knowing needed in the moment, but arranged according to its intrinsic order. He pictured the parts of the song as if carved in stone, symmetrical in time as the hieroglyph's marks were symmetrical in space. Legendary tales were transmuted into allegorical myths and epic cycles. Consider Moses; consider Homer.

Chirography. The art of writing by subtlety of hand, rather than by strength of arm. Man saw that clay would hold a mark as well as stone, and later that pigment brushed onto tree-bark dried faster and weighed less than either. As he wrote more, and more swiftly, he reduced picture to character, boiling down the words first into constituent syllables, then into atomic elements. The writing no longer captured the meaning of the discourse, but the discourse itself; the reader no longer had to reconstitute its sense, but only its sound. He began to worry that much of what had been written was only the occasion for so much hot air.

Now literature in the truest sense was born. His words had always sought to be mellifluous for the sake of being memorable. But now the page remembered the words for him, and beauty could be for its own sake, or, more precisely, the words could be shaped to be beautiful so that the page would be deemed worth transcription. Which is to say that the words could have a style. From "stylus"—the author could be known from his turn of phrase just as well as from how he turned the corners of his letters. The words no longer belonged to the common store of wisdom, but rather were attributable to one man, whose character could be known and judged from the sound of his characters, and how their arguments sounded in dispute with one another. Consider Plato; consider Vergil.

The codex. Binding up the scattered leaves of parchment into an orderly array branching from a single trunk. Man sewed together into the same text as many words as could be fit onto dozens of scrolls; he imagined a codex containing the entire cosmos. Instead of channeling a continuous stream of words for as long as the scroll lasted, the codex subdivided them across hundreds of pages and lines, into numbered chapter and verse. He saw things as infinitely articulated, and extended this habit of articulation further through the newly invigorated art of punctuation. Intended at first to facilitate the fluent sight-singing of liturgical texts, it accidentally enabling as well their reading in silence.

Within these codices he inscribed not only the old fluid, ironic, reasoned discourses, but also newfangled chiming, analogical, authoritative catechisms. Rhyme served not only to make the words memorable, but to amplify the interconnectedness of things apparently far apart; even the prose rhymed in sense if not in sound. Conceptual dissonances, rather than undermining trust in what had been said, served to emphasize its mysterious truth, how a word could apply even where its application could not be understood. The words no longer had to carry their reasons with them, for words were always a cross-reference to their other uses, and their having being found elsewhere in the same order in the same codex was itself a reason in their favor. Consider Thomas; consider Dante.

Typography. The art of printing the same tokens in arbitrary order and quantity by rearrangement of reusable type. Inert in itself, but explosive combined with the alphabet's reduction of types from a few thousand to a few dozen. Now a myriad of copies required little more effort than one. Now "a copy" was not a sequence of transcribed words slightly permuted through scrivener's errors and idiosyncratic spelling, but rather a bound volume precisely identical to every other, any typo uniformly marring the entire edition. Now characters were precisely identical to every instance of themselves; new character-forms almost impossible to invent; image and text rigidly demarcated from one another.

With so many books in the world, seemingly everyone could learn to use them. Books were written both to appeal to and to stand out from their new patron, the crowd, to avoid the fate of being bound only never to be read. Too, with so many books in the world, a single volume could no longer be imagined to contain the world, but only a view of it. Instead of showing mind and world to share a structure, books suggested a chasm between them foreclosing perfection and making personality possible. Finally, with so many books in the world, their format became standardized. Word-forms became frozen in dictionary amber, and the first geniuses to publish would shape the language for all time to come. Consider Cervantes; consider Shakespeare.

The telegraph. "What hath God wrought," the first phrase sent by wire, stands synecdoche for a myriad of nineteenth-century technological advances. Pulp paper and the penny press, swelling voluminously the quantity of newsprint; the telegraph, providing worldwide fodder for the newspapers' new pages; the typewriter, erasing the intermediate step between mind and printed page; the phonograph, bypassing the written form entirely; the radio, severing the last tenuous link between communication and physical contact. By the early twentieth century words seemed both omnipresent and obsolete. The world had been replaced with words about it, and more words about these words would be mere superfluity.

Not that the crafting of words ceased—but it became a rearguard action, a fight to give verbal form to the unending torrent of verbal content. The author was compelled to recognize the inarticulate crowd as both present obstacle to and present arbiter of the success of the formal enterprise. Some submitted to the crowd's authority and so found themselves at its head, shaping words that would inflame the crowd to world-historical deeds. Others placed themselves in opposition to the crowd, and sought the word's authority from some other time than the present: in pseudo-hieroglyphic mysticism; in the judgment of history; in visionary philology. Consider Goethe; consider Joyce.

Signal. No longer merely what moved along the wire, but an all-pervading field. Everything could be encoded in and decoded as a signal; everything was information, computable and computed as a sequence of zeroes and ones. Even speech was but one variety of human signal, along with gesture, countenance, pheromone. Signal came prior to and required nothing human, but rather constituted the human, running across the neurochemical pathways of the brain as it did between the clouds and out into infinite space. Signal never changed, only the way in which each separate self received it.

The signal contains (it is believed) every word that ever has or ever could be said. And so literature died, giving way to the circulation around the web of fashion and rumor, sketches of worlds whose form could not be believed, but could be fled to as a refuge from the signal's infinite memory. Whoever still wrote undertook the task with loathing, and pursued it only to the point where he no longer felt that his failure to write sent its own even stronger message. Every word was already a tweet.

Interpretation

Through what categories does man understand the world and decide his own place within it?

Animist superstition. At first man never said that everything is connected, for he had no concept of "everything." Rather: each thing directly linked to each other. Each thing animate, its spirit speaking to the spirits around it. Each thing a reverberating word. Man but one more reverberation, no different in kind from wolf or deer. No kinds, only uncanny correspondences. To ignore these correspondences: to act at one's own peril.

Cosmic religion. In time he pictured everything in the world connected, which is to say that the world itself became for him a thing, to be imagined separate from the various things within it. They became the shadows it casts, the shape its order imprints upon the chaos. Too, he now sorted the various things in the world into different kinds, each given its unity by its own invisible spirit. Each person, each family, each town, each realm, had its own tutelary deity, a hierarchy hovering over the visible. The bonds between visible and invisible, and subordination of the former to the latter, required regular reinforcement, lest order degenerate into chaos.

Political philosophy. No longer could man be content with cosmos asserted as occult unity; unity required public articulation and verification. Putting the order into words shifted the order's meaning: the invisible hierarchy no longer paralleled the world's structure, but explained how that structure cascaded down from a single fundamental abstract principle to which each element of the visible world was equally subject. Too, confirming that the order continued beyond the glimmering surface shifted the endeavor's emphasis: man sought to identify, not the ordering spirit, but the matter that it ordered, above all his own matter; he identified himself as the thinking living thing. Although the task of articulation threatened to degenerate into an endless regression, and the task of verification into an aloof skepticism, it was clear that to act other than in accord with reason was irrational.

Sacramental theology. Man resolved philosophy's dilemmas by elevating will to a principle coeval with reason and unity in the constitution of both man and world. Not only did reason give rise to an obligation to act in accordance with it, but the conjunction of right reason and right will was constitutive of both. The Trinity solved the emanative regress with a single word: the visible flowed from the invisible because the invisible chose for it to do so, and it was right so to choose. Similarly, it solved the problem of skepticism by giving the skeptic a defined place in the world: he was with Satan, trapped in an inward-curving spiral away from true order, and posed a danger ultimately only to himself. The Incarnation of the historical Jesus perfected all three: the ordering word chose to be man; the choices of a man are analogous to those of the ordering word; and the most important choice of all is whether or not to participate in the ordering word's mystical humanity. Analogous only, of course, and herein lay the rub: the mysteries of God, Christ, and Church could not be fully grasped, and fell inevitably under suspicion of being mere mystifications.

Private rationality. As the haphazard and potentially hypocritical nature of analogical reasoning became increasing intolerable, man abandoned it in favor of determinate calculation. One by one the mysteries fell. Ecclesiological: instead of representing the invisible order through a visible community of believers, it was to be conclusively identified through the self's ineluctably private certitude as to the cosmos's clockwork mechanism. Christological: with the self now unaided by any visible other, let alone a society of fellow believers tracing its authority back to Christ, the significance of the particular man Jesus faded, until the insistence upon his divinity was only an arbitrary item of dogma. Trinitarian: the self's isolation dissolved the unity of reason and will; now man's reason served his will, above all by telling him to submit to the inscrutable will of the invisible. Apart from the name given to that will, theism became indistinguishable from atheism.

Humanist ideology. The self's private communion with the senseless cosmic order could not be sustained, not least because the content of "the self" was not self-evident. It had been derived by analogy with the invisibles postulated by theology, the triune God and the rebel Satan. Seeking a stable ground, he returned to those sources in more self-conscious form. Rejecting the postulation of invisible paradigms, he asserted that both man and world were not analogous to, but simply were, either the perfect unity of reason and will, or pure life-force striving again all externally imposed bounds. Or, at least, would become so, if man succeeded in seeing the world as if it were already what he imagined it might be.

Anarchistic idiocy. At last, man could connect nothing with nothing. The future promised by historicism and vitalism failed to arrive, save in a plane of unreal hypervisibility, where each thing was identified with its virtual representation. He saw no difference between man, daughter, dog, bot. The only law of reason he recognized was the ironclad calculus that determined every interaction; his only motivating desire was to escape this law by escaping interaction itself.

Persons & Performances

What objects does man recognize to represent himself and others? How does he charge their interactions with greatest meaning?

Even before he knew himself a person, man made himself a mask. A vessel for a spirit, a person who was not really there, and so was everywhere. In making a mask, man became himself personable.

The big man, and all men, wore the mask to the hunt or fight, where they became the death of the prey. Upon reaching its corpse they would honor its death-mask and release its spirit to flow through some other beast or man. Too, the big man, and all men, wore the mask to the sacred dance, where they became not only men and the big man, but Spirits, and the Big Spirit.

Man began to busy himself across distances. The person who was not really there would sometimes be an imagined god, sometimes a ruler enclosed within palace walls, sometimes a counterpart merchant in another city. In all cases, a patriarch whose children could not but obey the signs of his voice. They knew his presence from his seal pressed into clay by a cylindrical scroll.

Loyalty to the unseen authority would be demonstrated through ritual sacrifice, with the best of the offering given to the representative of the unseen. After the blood ran down the altar, filling its intricate engravings, the representative took the auspices. If the sacrifice was not maintained, the bonds of loyalty renewed with blood, none could know what would result: perhaps an unwelcome freedom; perhaps (and what might be the same thing) a wrathful visitation from the person scorned.

With coinage, man verified—not the identity of the fictional person, which was no longer in doubt—but the integrity of the material substrate. The face of the sovereign pressed into a gold disc guaranteed its weight and purity, or at least punished their violation. "Exactness of design was to deter imitation; mutilation if that failed." Each coin a sign of the sovereign's sword, kept sheathed out of tolerance for his subjects.

The integrity of that sword was seen in the sovereign's public dispensing of justice; its strength, in triumphal processions; its tolerance, in the tragic dramas that developed from the religious rituals his subjects no longer took quite so seriously. Their subtle ironies may have called into question the righteousness of his rule, but they did so only to answer the question in the affirmative. These performances never forgot their sacrificial origins, always concluding with formal procession from theater to temple.

Man wore a coat of arms to declare himself—or decline to do so, choosing rather the black surcoat of the anonymous knight errant, with his face to be revealed only after trial by combat. Even when seen, the meaning of the coat was emblematical, its precise decryption known only to the bearer and his friends. The coat's centrality was the result of sovereignty being distributed throughout the population, each man through violent action embodying the divine law of peace. The pope, too, has his papal arms.

If proper interpretation of other persons inevitably risked violence, it was still figured as an essentially peaceful endeavor. The paradigmatic performance of personhood was the bloodless sacrifice of the Eucharist, at which Christ's invisible presence could be read in the pale wafer elevated for all to see, and the pax could be exchanged between prelate and prince and on down the social hierarchy. In the fields outside the commoners gathered around to put on rude mystery pageants, showing in comic light the obtuseness of Christ's torturers, the pride of the scribes and Pharisees, the ambivalence of Pilate.

Under the flag man rallied around a simplified image of his nation's spirit—or declined to do so, flying a neutral's flag until the last minute and then raising the Jolly Roger. Adopting the opposite of the Black Knight's modus operandi, the Pirate acted as an agent of chaos in a world increasingly enmeshed in man-made laws. One was born into a nation, but could always leave it; the pirate nation was universal.

The nation's spirit could be seen around the person of the monarch in the pomp of the courtly masque, and heard in the stream of rhetoric issuing from the pulpits of the national churches. Its content was most fully articulated in historical dramas depicting the spiritual struggles of the sovereign's forbears, and in romances depicting the moral virtues expected of each citizen. While heroism lay in ordinary loyalty, its success often depended on pirate attack or other extraordinary maritime disaster. These fatal ironies were not lost on the audience, but that audience saw its own face on the other side of the stage, and knew to keep its response within bounds.

Man ascribed each logo to the imaginary penmanship of a corporate body, a legal person, a commercial brand. Its putative signature verified the reality of the goods upon which it was mass-imprinted, but not by the physical impossibility of forgery; to the contrary, its mimetic power depended on ease of reproduction. Rather, it proved itself by legal prohibition, a matter of trademark. To "pirate" now meant only to defy such legal fictions.